Introduction to Project Management

Introduction

The organisation of exhibitions always takes the form of a project. Project management therefore plays a central role in the process. If the aim is to organise an exhibition well, a good basic understanding of project management is important. In view of this an introduction is included below which provides a broad overview of the subject. For a more in-depth understanding, please refer to the many publications available in this field.

What is Project Management?

The concept of management can be defined in different ways. It is often described as:

“the systematic and integral control of processes“1

Wikipedia sums it up as:

“one or more people setting in motion the controlled execution of activities aimed at achieving a predetermined goal“2

Management is used in a variety of areas, ranging from human resource management, to operations management, strategic management, marketing management, financial management, ICT and resources management, change management, quality management, information management and project management. Project management differentiates itself from general management by its temporary nature and the fact that there is a predetermined goal. A concrete result must also be achieved to which parameters are given in terms of money, time and other resources, such as manpower. Project management can therefore also be defined as:

“the systematic and controlled steering of a single result-orientated process which must be executed within given parameters of time, money and resources, on the basis of pre-defined objectives.“3

There are certain essential elements that determine whether something is a project:

- The achievement of a concrete result;

- A unique and one-off result;

- A definable start and end point;

- An internal (usually, the management of an organisation) or external client.

Projects can take many forms from simple ones such as organising a holiday or a dinner with friends, to extremely complex ones such as the building of a passenger ship or the construction a high speed train. Projects do not always need to have a material product as the outcome either. Writing a policy or doing research can also be conducted on a project basis. This model focuses on projects in the field of spatial communication, such as the establishment of a flagship store, the implementation of a trade show stand, the organisation of a science centre or a pavilion at an international exhibition, as well as the establishment of a permanent or temporary exhibition in the heritage sector.

Projects generally flow from the work of a permanent organisation, such as a cultural institution, a government organisation or a business. Through the running of such an organisation needs can arise for unique or one-off products like, for example, a customer survey, a feasibility study for a new location, the development of new products, the construction of a new building, a re-organisation, a new policy, etc. In many settings unique or one-off products form (a part of) their end product, for example in museum exhibitions or designs for exhibitions at a design agency. Since projects do not often form the core business of an institution or business and are an anomaly for them, much of the essential know-how is lacking. Many projects are therefore wholly or partially carried out by external specialists. When the project is completed, the product returns to the existing organisation. This is aimed at maintaining the product, which is often of a routine nature and can be carried out according to established procedures.

Control aspects

Above project management is described as the systematic and controlled steering of a single result-orientated process which must be executed within given parameters of time, money and resources, on the basis of pre-defined objectives.

In order for a project to be systematically steered and controlled the following five aspects must be controlled in an integrated and coherent way: time, money, quality, information and organisation.

Time

The aim is to deliver the project on time and this encompasses structuring the project into phases, the establishment and monitoring of plans and, where necessary, the making of interim adjustments to these plans.

Money

This refers to:

- The preparation of forecasts for the costs to be incurred: In the beginning of the project this is often based on general experience expressed in prices per square metre and ratios. As the project becomes more solid, these forecasts become more precise and detailed, resulting in more and more concrete cost estimates.

- The covering of the costs: This has to do with income sources like available budget, expected revenues (e.g. from entrance fees at an exhibition) and, if necessary, from fundraising or other forms of financing.

- The constant monitoring of cost developments, costs estimates and budgets: These are checked against the (revised) project budget and if applicable against revenue from fundraising (budget control).

Quality

This means:

- Assessing the quality and ambition of the project: Quality refers to substantive and technical requirements and is a result of the available money, time and resources (e.g. amount of manpower and expertise). In determining the quality of structural projects such as exhibitions, aspects of sustainability can be involved. The quality requirements need to be realistic. In practice it often turns out that a (much) too ambitious level is sought after for which the budget is altogether too low (wanting a Rolls Royce for the price of a Volkswagen), that the time is too short (wanting it done yesterday) and/or the resources are insufficient (having only a group of volunteers with little experience and knowledge of the essential project subjects). In exhibition-making especially, the costs, time and essential know-how required to achieve a professional product are often underestimated by clients. Having quality requirements and ambition levels that are too high at the start can often lead to the failure of the project and frustration amongst those involved. Depending on the knowledge and experience of the client, it is worth setting realistic quality requirements and establishing them through good consultation between the client and the contractors. The expertise and experience of the contractors can be used in this way to come up with a feasible level of ambition. Incidentally, “quality” also has to do with achieving the goals set in advance. An exhibition that gets its objectives from selected target groups has in that sense, a good level of quality.

- The interim checking of the quality level: This is tested against the level that has been determined at the beginning of the project. It is recommended that the detailed project plan – called the Provisional Design in exhibitions — ensures that it represents the 100% solution in terms of achieving both the project objectives and the feasible quality for that project. In practice, it often turns out that during the subsequent execution and implementation of the project various adjustments need to be made. In direct consultation with the client, usually in the context of “construction” meetings, these adjustments can be discussed and checked against the detailed project plan. In general, adjustments lead to a reduction in quality. Experience shows that a project that gets 80% of the desired quality is performing well. Quality control must also be realistic. Adjustments should be possible, provided they are not of such a nature that the whole project or parts of it fall below the level where it is no longer certain that the objectives of the project will still be met.

Information

Information management is divided into two parts. Internally and externally oriented information control.

Internal Information Control

This is to ensure that everyone involved always gets the information that is relevant at that time to carry out their contributions to the project. The internal information management can take place in various ways such as:

- The production and discussion of reports: This mainly concerns reports where the results of the work and conclusions from a project phase are recorded, the so-called ‘decision documents’. Given the importance of the ‘decision documents, it is essential to record discussions in reports.

- Giving briefings: These may be given to externals and/or team members on the tasks to be carried out by them.

- Holding regular project and/or construction meetings: In practice, a frequency of once to a maximum of twice a month is realistic during the preparation and design phases of an exhibition project. During the construction phase, a higher frequency is effective of at least 2 per month to sometimes once a week (in the final stage).

- The making of meeting reports with action lists: For good information management it proves effective when project team members make a brief correspondence report of discussions they have with externals which is then circulated. Archiving records and mail correspondence in project documentation is of vital importance here. In this context it is good to appoint a project secretary who carries this out and is accountable for it. In order to set up proper project documentation all documents should contain a version number, the date and the name of the author.

- Informal correspondence via email and telephone: Constraint should be observed with email correspondence. Often a question to a project associate gets sent to all project members, who then in turn reply to everyone. When this happens in an uncontrolled way an information overload is caused that is not only ineffective, but often arouses irritation too. With rampant email correspondence you often hear talk of ‘email-mania’. The idea that everything can be controlled via an “email” is becoming outdated. Email is an efficient tool for internal communication, but also has its limitations, particularly in terms of the interpretation of text (miscommunication), and relating to the time spent on it. A consultation on a particular subject can be communicated considerably more effectively in a phone call or a short informal 5 minutes meeting than in an email exchange lasting 30 minutes. The conclusions can then be confirmed via an email. In short, a selective use of the various informal forms of communication is necessary for good internal communication.

Internal information provision is often seen as a responsibility of the project manager. Even though he has a coordinating and supervisory role in this, all team members have a responsibility for information provision. All the work the team members carry out and the consultations they have should be informed by the basic principle: who needs to know the results of this? In order to avoid the above-mentioned email-mania this needs to be carried out in a very selective way.

External Information Management

This refers to the information about the project and its progression to third parties outside of the project group and client. Often external information management is a task of the client. In exhibitions this can form part of the general and/or the project-targeted promotion of the commissioning institution or company. Mounting a project promotion campaign right from the start following the developments of the project can contribute significantly to its success. Furthermore such campaigns have been mainly applied to larger exhibition projects such as the refurbishment of a museum.

External information control can also be directed at their own organisation or business. Project progress reports may be included in:

- meetings of the board of the institution or company;

- information bulletins for partners, such as friends of a museum, or a company’s customers;

- communications to staff, whether or not as part of a regular appearing newsletter.

For the conduct of internal and external information provision it is advisable to set up an Information Protocol at the beginning of the project. Arrangements can be made herein about who will be informed about what and at what moment and which communication channels will be used as a preference.

Organisation Control

This aims to ensure that during the project it is always clear:

- who are involved in the project;

- what their duties, responsibilities and powers are;

- what the decision-making structure is?

Those involved in the Project

The Client

The client is ultimately responsible for the project and has the task of taking final decisions concerning the project, encapsulated in phase results and final deliverables. A client can be either internal, i.e. coming from within the organisation, or external. Usually, the client functions as the director or head of a department, e.g. from the communications department of a large company that wants to run a stand at a trade show. As an exception to this is when the board of an institute or foundation is the client, for example in a museum run by volunteers. In commercial contexts the term customer is also used.

It is highly important, especially when working for an external client, to be very clear about who the actual client is. The person who has the first contact with the contractors and gives the project briefing, is often not the client, but the contact person who has been asked to arrange these things. As a contractor it is good to ask if you are unsure who the actual client is. In practice it is not always clear within the client’s organisation itself and must be sorted out. Uncertainty about the client can cause significant delays in the progress of the project, because it is unclear who should make the final decisions. In extreme cases it can even lead to the failure of the project. Anyway, it pays not to think too lightly about the commissioning body. If a project is managed unprofessionally at this level, then this can lead to long delays and frustration at making progress. Common problems with commissioning bodies are:

- insufficient knowledge of project management and how projects develop in phases and should be managed:

- unwillingness to take decisions or the postponement thereof;

- returning to previous decisions;

- taking decisions on the basis of personal emotions or by imposing decisions rather than on the basis of business considerations connected to the objectives of the project.

The Project Leader[4 The extent to which tasks, responsibilities and powers are delegated to the management of a project is not always the same. The job title of the leader is somewhat linked to this. A guideline for the job titles can be as follows: project manager (large and complex projects, usually a management specialist), project leader (more mundane projects, strong emphasis on both the content and management aspects), project coordinator (primary competence to coordinate disciplines/activities; often is it someone from the middle of the team that takes this role). In practice, these names are often used interchangeably. For our purposes here, we have adopted the term of project leader.]

The project leader is responsible for the implementation of the final outcome of the project in terms of objectives and fixed quality levels. To this end, the project leader:

- manages the project and project employees;

- monitors the objectives and any target group orientation;

- ensures the phase results are achieved;

- plans and structures the project;

- is responsible for the proper control and monitoring of the five control aspects through establishing and monitoring work plans, budgets, organisation charts for the project and any information protocols.

Usually the project leader directs the project team, is present at project meetings and maintains contact with the client. The managing and supervision of third parties (subcontractors, suppliers and service providers), as well as external information services often falls under his/hers responsibilities.

Project leadership takes many forms depending partly on not only the actual nature and scope of the project, but also on the culture of the institution in which the project takes place and the personality of the project leader. For large projects, and also within larger hierarchically organised institutions and businesses, the style will be more ‘dirigiste’ and business-like in which the overall responsibility and thus the decision-making lies more directly with the project leader. For smaller, more creatively oriented projects such as exhibitions, the management style is often of a more coordinating and stimulating nature where the project leader takes decisions based on corporate outcome-related reasons from the team, but where necessary also on their own responsibility. Central to this idea is to optimise the final product by always allowing space for the creativity, knowledge and experience of professionals within clear frameworks.

The Project Team

Within a professional project, the project members are chosen on the basis of business considerations, i.e. according to the essential know-how needed for the project. This can vary by phase or group of phases. In the early phases of exhibition projects content-related and creative skills are mainly desirable. When the project plan is ready, in the form of a ‘provisional design’, and the exhibition project is in more of an implementation phase, more architectural and specific know-how is required, for example for the production of audio-visual programmes and interactive exhibits. The project team is also often modified and extended in later phases.

In recent years there has been a tendency to involve builders and manufacturers from the start of the project, in an effort to anticipate the essential know-how required in later phases. Although these specialists do not have a direct role in the beginning phases, it may be that through their knowledge and experience in the field of organising and realising exhibitions they make positive contributions to this first phase. This method also has the advantage that it can quickly build a good team spirit and increases efficiency as parties do not need to be integrated at a later stage. The disadvantage is of course choosing parties at an early stage who will only play an active role in a later phase.

With large exhibitions projects this way of working leads to so-called consortia. Here you find a number of companies who are specialised in different areas committing themselves to tender for the project as a service provider. These are often alliances of communication-/content-oriented companies with designers and exhibition construction companies. Sometimes museological and audio-visual specialists are also a part of such consortia.

Finally, it should be noted that a team of renowned specialists are not the most appropriate team per se. The best result is achieved by a team of co-operating specialists who understand their duties and roles within the team and respect those of others. Projects dominated by one specialist will ultimately gain a more one-sided result, thereby only fulfilling part of the objectives.

Tasks and Responsibilities

Following on from determining those involved in the project is the essential step of recording their duties, responsibilities and powers. The starting point here is that one does not acquire responsibilities without the corresponding powers. A well-known example is the project manager who is responsible for the project budget but does not have the authority to make changes within the approved total budget or to negotiate partial budgets with third parties. The absence of these powers erodes not only his task as authorising officer, but also creates an inefficient course for the project because every change must be submitted to the client. If the budget is such that the client cannot or will not hand over budget responsibility entirely, it may be decided to give the project leader a certain amount in order to allow some power of decision-making. Also with regards to the hiring of third parties and the hiring of personnel similar arrangements can be made.

Seeing as the project leader has the central role in the project, there follows below a summary of the most important powers that a project leader must have:

- the power within agreed budget margins, plans and information protocols to make changes to time-schedules, budgets and internal information provision;

- the power within the approved framework of the project to give assignments to the project staff and to negotiate with contractors, service providers and suppliers.

Giving an overview of the powers that team members should have is less simple. Given the differences as to the content of their duties, they should be determined on a case to case basis, depending on the responsibilities they have.

Decision-making structure

Connected with the establishment of the above mentioned duties, responsibilities and above all authority, the decision-making structure must be made clear. Usually, the project organisation is established in an organisation chart or organogram. If possible duties and responsibilities should also be specified on this. Powers and mandates may be recorded in separate documents or (especially for external project staff) in contracts.

Project Steering

The steering of the above five control aspects is strategic and is led by the objectives set at the beginning of the project and those which should be achieved by the implementation of the project. In order to carry out the process within “given constraints of time, money and resources”, there are three distinct project steering steps:

Determination of the project parameters

This relates to the determination of the basic principles of each of the five control aspects at the beginning of the process. This concerns questions such as:

- how much time is available in relation to the desired delivery date;

- how much budget is available;

- how the project will be structured in terms of phases;

- what the realistic quality requirements and ambition levels are;

- how internal and external information services will be arranged;

- how the project organisation will be set up.

Progress Monitoring

This takes place throughout the project by means of project construction meetings. The phase results play an important role in this (see paragraph below). The project results up to a certain point are always checked to see whether they still fit within the basic principles of the 5 control aspects laid down at the beginning of the project. For example, with regards to a proposed project plan:

- whether it is implementable within the remaining time;

- whether it still fits within the budget;

- whether it still meets the quality standards laid down within the framework of the project;

- whether given the nature of project, new/other individuals or groups should be briefed;

- whether the correct professional disciplines are still represented within the team;

Adjustments

If during the monitoring of progress any deviations are observed about one or more of the control aspects, this should be addressed. This can be done by changing the desired result in such a way so that it falls within the parameters or by changing the parameters or, rather, the standards; for example by increasing the budget, by postponing the deadline and/or by adjusting the requirements for quality.

Phasing and Structuring

Phasing

To implement a project a great deal of decisions need to be taken. It is important that these are taken:

- in a meaningful way, i.e. in a sequence that leads to an efficient project process; for example, with an exhibition project by first determining the content and target audience and then determining the form choices;

- in an efficient manner. It states above that the client is ultimately responsible for the project and thus for all choices that must be made. It should be clear that if all decisions have to be taken in direct consultation with the client, the project process will be greatly slowed down.

In order to achieve an efficient and manageable process, projects are phased. After each phase is completed, a report is written in which the choices made in those phases are summarised. These so-called phase results, which have the character of project team proposals are submitted to the client for approval and form the formal decision-making moments throughout the project process. In general these phase reports include the following:

- the status of the report in terms of the position it occupies in the phasing of the project process;

- a description of the project product. As project completion approaches, this description will become more concrete;

- the state of affairs of each of the five control aspects of time, money, quality, information and organisation:

- a forecast of further development, for example regarding time the planning, regarding money a budget. These will become more concrete as the project progresses;

- any proposals for changes, such as a budget increase or a revised project organisation.

The client checks the phase reports against the parameters laid down in earlier phases of the project. The client can approve, amend or reject the phase results. After approval or after adjustments such as amendments the next phase can be started. These approved phase results form the parameters on which the results of the next phase are tested. Thus a method is created in which the project team can work relatively independently and the client keeps control over the process and can make adjustments where necessary.

If rejected, a situation arises in which it can be examined whether the parameters are too restrictive in order for the expected result to be achieved or whether the right team is working on the project. It should be appreciated that in many cases rejection will lead to a delay in the project or even to termination. Although termination of the project can be extremely annoying, especially if it happens in one of the first stages, it can also be seen as a positive. After all, a project, which is not likely to meet expectations is better stopped in good time.

Standard Phasing

Over the years in which project management has developed as a discipline, a standard phasing has evolved. This is based on the following phases 4

Preliminary phase

The Initiation phase has an exploratory character and can be seen as a preliminary pre-study phase. At this stage there is not really talk of a project, but more of an idea that someone has or a problem needing a solution. The initiators, often employees of the institution or company, submit the problem or idea to the management team. If they see something in this problem or idea, it may be decided to investigate the project idea further. This involves a first exploratory study of the parameters of the project, such as:

- a more precise definition of the problem or description of the idea;

- an initial description of the possible end result;

- possible target groups;

- first estimates of necessary resources, such as budget, facilities, time and manpower;

- a review of existing or proposed policy objectives.

The result of this phase is the decision to actually proceed with the project or to desist. The review of the policy objectives will play an important role in this.

Definition Phase

In fact this is the first stage of the project. The exploratory basic parameters which were under investigation in the previous stage will now be finalised, possibly after further investigation. At the end of this phase, the project objectives, quality requirements and possible target groups are clearly documented for all concerned. It is also pointed out within which constraints the project will be completed in terms of time, money and resources. An Action Plan indicates how the project will be structured in phases.

Design Phase5

In the definition phase the goals of the project were formulated, in this phase it is considered how these can be converted to a concrete plan for the result/product of the project; the project plan. The project plan forms a detailed ideal solution for the “problem” as defined in the definition phase in terms of objectives, quality requirements and parameters. Interestingly, however, the same problem often has several possible conceivable solutions that are more or less evenly matched, although each have their own advantages and disadvantages.

Preparation Phase

After approval the project plan can be elaborated upon and made suitable for implementation. These are mainly technical elaborations. At the end of this phase, all the final choices have been made. For construction projects, such as exhibitions, this phase is concluded with a production programme, also called the operations or specification plan, possibly supplemented by drawings.

Implementation Phase

In this phase on the basis of the elaborations of the development phase the “product” or “result” of the project are implemented in a practical sense; for example the construction of an exhibition, or are in progress — for example, a reorganisation. With the delivery of the “product” the project is now, in the narrowest sense, over.

Follow-up Phase

The implementation of the project does not signify the end of the project in the broadest sense. The follow-up that takes place in this stage where the product is used, is designed to keep the project result in position and to possibly improve upon it. Follow-up can take different forms:

- maintenance, especially in construction projects such as exhibitions;

- monitoring, for example by means of user evaluations, to examine whether the project actually achieved its objectives and the desired quality level;

- adjustments and modifications based on shortcomings and defects;

- making adjustments based on new insights and techniques, particularly with long-term use of the project results.

In addition to the monitoring and evaluation of project results, the procedure of the project can also be evaluated at this stage. This involves questions such as:

- was the project completed within budget and if not, where did it go wrong6 It should be possible on the basis of this to make a final statement of accounts for the project.

- how did the planning go? Were there time overruns and how could these have been prevented?

- how did the partnerships and internal communication go and are there improvements that can be made, for example through better project organisation?

A comprehensive product and process evaluation preferably recorded in a formal evaluation report provides project experiences and data which can be used for subsequent projects. With systematic use of this empirical data, project work can be seen as a cyclical process where experiences from previous projects are sources of knowledge, ideas and improvements for new projects.

Structuring

Phasing structures the project. This structure does not always follow the standard phases described above but may vary from project to project, depending on the nature, size or characteristics of the project. Thus for the benefit of, for example, construction projects:

- the design phase can be divided into a research and planning stage,

- the development phase into a definitive design and specification stage,

- the implementation phase into a prefabrication and site-specific construction or installation phase

For smaller projects, such as temporary exhibitions, one can distinguish in the follow-up phase between a use- and concluding phase. In projects for the government, preferred models may be imposed upon contractors. Thus contractors in the EC should make use of the Integrated Approach and Logical Framework that the EC developed especially for its contractors to use 7

The introduction to phasing [(introduction to phasing)] will discuss a phasing model specially designed for exhibition making. Here some variants are pointed out and reasons for applying them. 8

Action Plan

Because the needs of every project may differ, it is essential that when planning any project we think about how it can be structured. Use can be made here of previously developed phasing. The starting point here should be that the project structure is clear, meaningful and efficient.

When planning a project so-called go/no-go moments can be employed. These are phase results where the basis on which the decision to proceed with the project or not have been established in advance. Go/no-go moments are generally tied to the first phases of a project, because the investment in time and money is still relatively limited. The incorporation of go/no-go moments is frequently associated with fundraising. This allows an exhibition project to decide to enter an intermediate phase of fundraising after putting together a project plan (called a provisional design for exhibitions). When planning a project, it is decided then that if this phase does not achieve the desired result then the project will terminate. In such a plan the costs for the making of the provisional design and the fundraising are deliberately seen as risk capital or pre-investment. In general such an investment is bound to a fixed amount.

Other reasons can also lead to a go/no-go approach. For example, whether multiple parties will participate in a project or not. A project proposal must then be created and submitted to the desired partners. If too little is seen in the project then it is a “no-go”.

The phase results, any possible go/no-go moments and the structure of the project in the form of the different chosen phases, together with any justifications of the choices made, are all summarised in an Action Plan.

Project Management and Permanent Organisations

Earlier in this introduction it was stated that projects often result from the work of a permanent organisation, such as a cultural institution or a company. In practice, the implementation of projects by or within a permanent organisation is not without problems. Seeing as exhibitions are generally organised with the direct involvement of a number of staff members, and as more and more institutions and companies are switching to more flexible project work, here is a brief look at these problems.

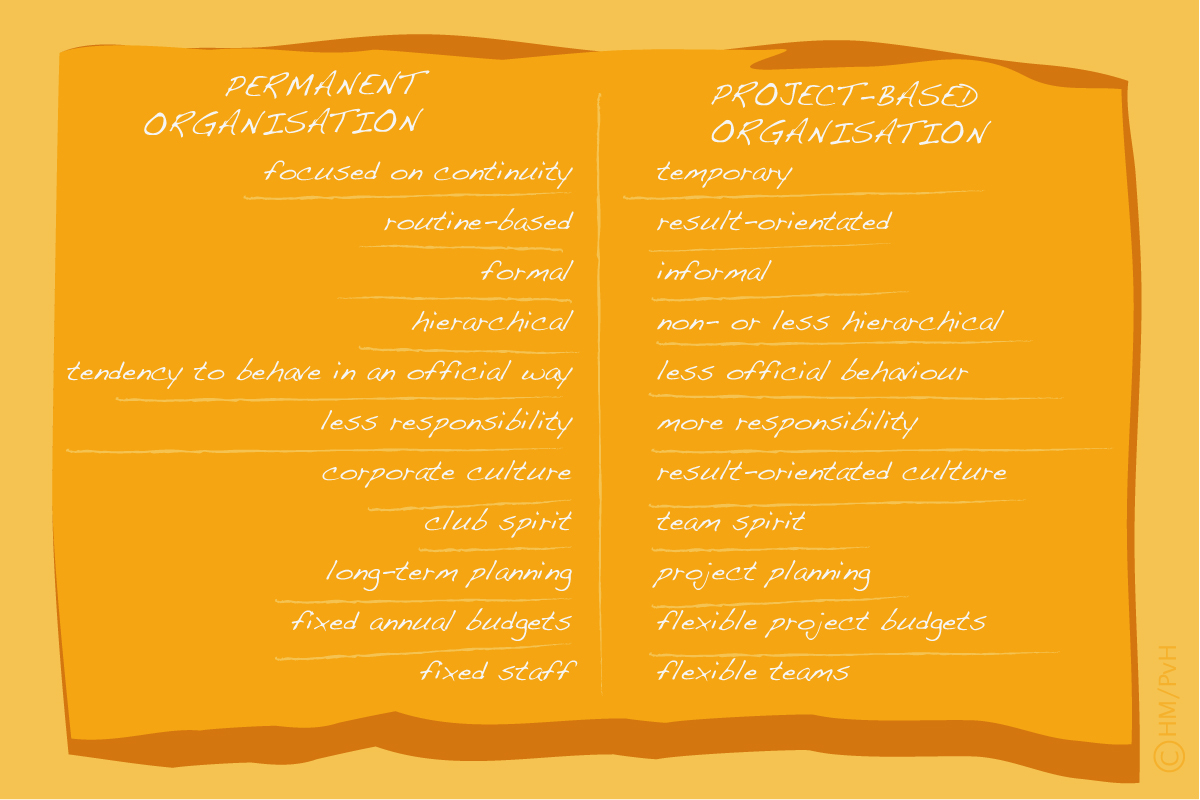

A major reason for the emergence of tensions between a permanent and a project-based organisation is the difference in culture9 In the diagram below several differences are shown between a permanent and a project-based organisation.

Diagram: Differences between permanent and project-based organisations (author Han Meeter)

In summary it can be stated that through its one-off result-oriented nature, a project-based organisation has a less rigid and formal way of thinking and acting. This is reinforced by the fact that project organisations are generally small and flat. They often involve a limited number of people who work closely with each other and differ little in terms of expertise and level of development. The project manager is often a ‘first among equals’.

Characterological differences also play a role. One will feel more at home in the clear, often well-controlled environment of a permanent organisation; the other more so in the more fluid and uncertain world of working constantly on different projects. Partly because of this, it is not easy to introduce project-based work into permanent organisations and team members from the permanent organisation often function less well in project teams.

In addition, a common problem is the so-called career-conflict. This may occur if a member of a project team comes from the permanent organisation. On account of the fact that the structures of the project organisation and that of the existing organisation will intermingle, tensions may arise, especially if the team member is linked to the project part-time and is therefore serving different interests. In fact, the project employee has two bosses, his head of department or director and the project manager. Both have their own distinct interests and will expect that the employee will be more favourably committed to themselves. The conflict is aggravated by the employee being dependent on his “boss” and close colleagues from the permanent organisation for his career and the working environment. For a good working environment and assessment of his performance in the project team, he is dependent on the project leader and project team members. 10.

In order to avoid a career-conflict, the responsibilities, powers and duties of these workers should be clearly regulated, both for their work for the permanent organisation and for the project organisation. A clear positioning of the project within the whole organisation is also important. Not only will a project that is of recognisable significance to the organisation be able to count on more support from the staff of the permanent organisation, but also this will clarify how the project organisation is inserted into the permanent organisation and what consequences this has for the employees who are members of both parts. In this context the tasks and powers of the permanent organisation’s management and those of the project manager can be adjusted with respect to the employee in question. Here, powers on a functional level (how does the employee fulfil his obligations and what are the consequences for his career) can continue to lie with the manager, whilst at operational level (when work is to be performed when) the responsibility for the duration of the project is placed with the project manager. The latter can report to the manager at the end of the project about the performance of the employee in the project and he can take this data for use in performance appraisals. For intermediate problems with the functioning of the employee in the project, the manager should be consulted. Thus there arises a clear division of tasks between the employee’s two bosses where it is clear who is responsible for what.

Where possible, a part-time commitment to the project should be avoided. This will, however, be difficult in the majority of cases. It is important in a part-time commitment that the employee has sufficient time to contribute to the project. Due to a lack of experience with project-based work, many executives in permanent organisations often underestimate project work. All too often employees must do the project “on the side”. When the permanent organisation has insufficient resources available to make the employee free for the project, this may have disagreeable consequences for both the permanent organisation, the project and not least the employee. In such cases it is better to raise funds to hire someone in from outside the organisation. If this is not possible, it may be asked whether the permanent organisation is capable of carrying out the project and whether the possibility of not going through with it should be considered.

Corporate Culture and Project-based Work

One can distinguish between various cultures in permanent organisations. These can be summarised into four types, namely:

- power culture;

- role culture;

- person culture;

- task culture.

It should be noted that different cultures may be present at the same time in an organisation.

Project-based work fits in better with one culture than with others. It is therefore important that a manager who wants to introduce project-based work knows which culture(s ) is/are characteristic of his organisation. This is also important for a project manager to know. In this way he can make a note of the resistance he might encounter within the permanent organisation.

A more detailed description of each of the four cultures that we can see in an organisation will be given below. Archetypes have been adopted here which in reality rarely or never occur in pure form. Usually we find mixed forms dominated by one of the four culture types.

Cultural differences between organisations or departments are reflected partly in the following aspects:

- way of interacting with people — approach

- appreciation for certain situations / people — values

- formulation of the organisational objective — organisation

- adaptability in certain situations — response

- dealing with opportunities and threats — threats

In the following description of the four types of cultures, characteristic elements are provided associated with the aspects referred to above.

Power Culture

- approach: is defined by personal power or resource power

- values: characterised by personality

- decision-making: through force

- organisation: for personal goal achievement rules of the central man are important

- priority: to maintain power

- response: is straightforward to changes in the environment provided the authorities are included

- threats: size, the personality of the crown prince.

We come across power culture with many growing organisations in the pioneering phase and also with family businesses.

Role Culture

- approach: is characterised by following rules, lines of communication and authority; titles are also important

- values: subordination to rules, role fulfilment

- decision-making: on the basis of procedure and formal position

- organisation: maintaining order, clarity and peace

- priority: job/role/position

- response: has difficulty with changing situations

- threats: paper tiger/bureaucracy

The role culture is characteristic of traditional public authorities, but also for example in insurance companies. Within larger museums role culture is often dominant especially in management departments.

Person Culture

- approach: only when needed, therefore few permanent structures determined by, for example, joint capacity source (building, computer); little binding force.

- values: expertise and skills

- decision-making: by consensus or not, no subordination

- organisation: for talent

- priority: for skills/profession

- response: is unpredictable, i.e. all individuals

- threats: size and disintegration through, for example, method struggle

We come across person culture in many partnerships, for example, designers, architects, lawyers or doctors.

Task Culture

- approach: is defined by the task at hand, time relationship/person/work.

- values: skilled worker as do-er

- decision-making: on the basis of what is needed at this time for this task

- organisation: pooling of expertise, getting results, rules unimportant.

- priority: results

- response: is quick to change

- threats: all or nothing

Task culture is characteristic of, for example, contractors, exhibition contractors and producers of audio-visual programming. Also, public-oriented departments of larger museums often have a task culture.

In general it can be said that task cultures are the most project-friendly and role cultures the least. Person and power cultures are in-between the two.

- See also: Project Model Exhibitions, page 5 and Verhaar, J. Projectmanagement, a professional approach to events, page 14. ↩

- Wikipedia defines management as follows “The French word mesnagement (later ménagement) influenced the development in meaning of the English word management in the 17th and 18th centuries.” “Management comprises…leading or directing“and “derives from the Latin word manus (hand)”,“is a process of successive human activities. These activities can be divided into four groups: (1) on the basis of a vision and mission, defining a strategy and elaborating it through plans (translated into specific, measurable, achievable, realistic and time-bound (SMART principle) organisational objectives), (2) the structuring of the organisation, (3) directing the staff, and (4) checking whether objectives are reached. This process denotes the various constituent elements of management.” ↩

- Incidentally, there are several descriptions of projects and project management all of which amount to more or less the same. According to Verhaar project management is the “… steering of processes within a temporary organisation”, whereby project management is characterised by “… the systematic and integral control of the development of a creative idea into a tangible product or result” (Verhaar, J, Project Management: a professional approach to events page 14). Grit defines a project as “… a temporary roster of a number of people — usually from different fields — to achieve a fixed budget a predetermined goal” (Grit, R, Project Management, page 21.) ↩

- See also Grit. R., Projectmanagement, p. 26 — 29. Grit describes the phases based on the standard phasing compiled by the specialist project management consultancy Twynstra & Gudde. On their website there is a comprehensive publication on project management ↩

- The word design is understood in the general sense. It may also cover, for example, the creation of a policy, a reorganisation plan, a plan for the introduction of automation or for the description of a museum collection or for a script for a movie. ↩

- This is generally only concerned with budget overruns. However, even if the final bill shows a large positive balance, it may still be asked whether the project has been properly implemented. After all there was budget available to achieve a better result. ↩

- See also Manual Project Cycle Management: integrated approach and logical framework (sp 1993) ↩

- phasing models are also put together for other types of project. For example, Verhaar in Project Management 1, a professional approach to events, stage models for conferences, exhibitions, festivals and events, stage productions, video-/filmproductions and trade fairs. (Verhaar, J. Project 1, page 245 ff) ↩

- (Organisation) culture can be described as a system of implicit and explicit patterns of thinking, feeling and acting, where these patterns are carried out by the people who make up the organisation. Other terms that can be used are atmosphere, climate, values and norms. (See also Verhaar, J., Meeter. J., Project Model Exhibitions page 25) ↩

- See also Verhaar, J., Meeter. J., Project Model Exhibitions page 20 and Grit. R., Projectmanagement, page 44 ↩